VideoReView Project Overview 2016-2017

Empowering Teachers Through VideoReView is a NSF funded research and development project (#1415898) to enhance elementary science teachers’ attention to students’ science thinking. The VideoReView program involves teams of teachers in school-based, video-supported professional learning, and a technology to capture and study classroom videos.In the VideoReView program, teachers participate in a four-part sequence: PLAN, ENACT, STUDY, and MEET. First, teachers plan science discussions to lead with their students. Then, they enact the discussions in their classrooms and use a classroom-friendly technology—a camera and software tool—to capture the discussions. Next, teachers use the software tool to study and analyze videos of their science discussions, and to prepare video cases for deeper reflection. Finally, they meet with colleagues in teacher-led Video Clubs to discuss the cases, and to plan next steps in instruction.

VideoReView Research Overview

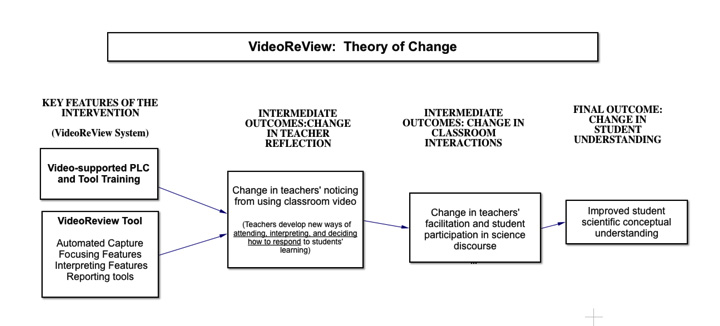

The VideoReView research investigates how school-based, video-supported professional learning helps teachers to notice students’ science thinking. The research is based on a theory of change in which teachers videotape science discussions, and then study the video on their own and with colleagues, with the explicit intent of understanding their students’ ideas and reasoning.This video study is hypothesized to increase teachers’ reflection on student learning, and teachers are likely to develop new ways of attending, interpreting and deciding how to respond to students’ thinking. Additionally, increased teacher reflection is hypothesized to improve classroom interactions. Changes in teachers’ facilitation and students’ participation in science discussions are expected. Improved teacher reflection and classroom interactions, ultimately, are hypothesized to increase students’ scientific conceptual understandings.

The diagram below depicts this theory of change, showing relationships between the VideoReView program, the intermediate outcomes of improved teacher reflection and classroom interactions, and the final outcome of students’ scientific conceptual understandings.

The research draws on prior work in using video to support teachers’ noticing of students’ thinking (e.g., Sherin, Jacobs, & Philipp, 2011; van Es & Sherin, 2010). This work shows that classroom video is a powerful means to help teachers attend to and make sense of their students’ ideas, and to respond in ways that can foster deeper student thinking.

The research draws on prior work in using video to support teachers’ noticing of students’ thinking (e.g., Sherin, Jacobs, & Philipp, 2011; van Es & Sherin, 2010). This work shows that classroom video is a powerful means to help teachers attend to and make sense of their students’ ideas, and to respond in ways that can foster deeper student thinking.

The VideoReView research investigates changes in four areas of teacher and student learning: (i) teachers’ noticing of students’ thinking while reflecting on classroom videos; (ii) teachers’ facilitation of classroom science discussions; (iii) students’ participation in science discussions; and, (iv) students’ scientific conceptual understandings.

Specifically, the following questions are at the heart of this research:

- Does participation in the VideoReView program improve teachers’ attention to and interpretation of students’ thinking, and pedagogical decisions based on students’ thinking?

- Does participation in the VideoReView program improve teachers’ facilitation of discussions to promote students’ learning?

- Does students’ participation in science discussions improve as teachers participate in the VideoReView program?

- Does students’ conceptual understanding improve as teachers participate in the VideoReView program?

The data collected to answer these questions, and the procedures used in collecting and analyzing them during the 2016-2017 study are elaborated in the Methods section.

The research findings from the 2016-2017 study are presented in the Impact section to show how the VideoReView professional learning program helps promote changes in teachers’ noticing of students’ science thinking during video study, changes in classroom discussions, and changes in students’ conceptual understanding.

References

Sherin, M. G., Jacobs, V. R., & Philipp, R. A. (Eds.). (2011). Mathematics teachernoticing: Seeing through teachers’ eyes. Routledge.

Van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. G. (2010). The influence of video clubs on teachers’

thinking and practice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 13, 155-176.

Methods

Participants in the first cohort – 2016-2017

Eight elementary grade science teachers from two suburban schools in Massachusetts formed the first cohort participating in the VideoReView professional learning program in 2016-2017. The teachers taught upper elementary grades (grades 3-5). They participated in the program for the first time. The VideoReView program was implemented separately in each school over approximately 10 weeks. Each school had four teachers and they led Video Club meetings in their respective schools.Procedure for Data Collection and Data Analyses

Think Alouds: Each teacher videotaped at least five whole class discussions that s/he enacted as part of the regular science curriculum. Of these recordings, the researchers focused on their first two and last two discussions. A member of the VideoReView team met with each teacher to support his/her study of videos of the four discussions. In these study meetings, the teachers were asked to ‘think aloud’, i.e., to comment on what they noticed as they reviewed their classroom videos. The study meetings were audiotaped and transcribed. The researchers then analyzed the transcripts to identify what teachers noticed in the videos, and how they made sense of their observations. The coding scheme used to analyze the Think Aloud transcripts is similar to that used in analyzing transcripts of teachers’ Video Club meetings as described below.

Video Club Meetings: Teachers participated in five Video Club meetings; in each meeting, two teachers shared and discussed video cases, and planned next steps in their teaching. These meetings were audiotaped and transcribed, and the transcripts were analyzed by the researchers to identify changes in what teachers noticed in the video cases, and how teachers made sense of their observations. Additionally, the teachers’ video cases were examined to determine what issues teachers discuss with colleagues, and whether these issues change over time. As mentioned before, the coding scheme used to analyze the Video Club transcripts is similar to that used in analyzing transcripts of teachers’ Think Aloud meetings.

Video of Science Discussions: The classroom discussions recorded by the teachers served as another source of research data. The VideoReView researchers analyzed transcripts of these recordings to identify changes in two aspects of classroom instruction: (i) changes in teachers’ facilitation of science discussions; and, (ii) changes in students’ participation during discussions. Specifically, the researchers examined how teachers respond to and take up students’ thinking, and how students engage with scientific concepts and practices during discussions.

Exit Interview: A member of the VideoReView team also conducted interviews with each teacher upon completing the VideoReView professional learning program. The interviews involved a set of seven questions to learn about teachers’ experiences during the program, and any changes that teachers perceived in their practice and in their students’ science learning as a result of the program. Transcripts of these interviews were analyzed to understand teachers’ self-reported shifts in teaching and planning discussions, attending to and facilitating students’ science thinking, reflecting on their own teaching, and shifts in their students’ science learning.

Student Assessment: Finally, students from two of the Grade 4 teachers’ classes took pre-and-post assessments before and after the science unit that was implemented for the duration of the VideoReView program. The science unit was part of the Inquiry Project curriculum, an elementary science curriculum covering foundational concepts related to matter. The pre - and post- assessments focused on core matter concepts from the curriculum. The pre-and post-assessments were identical in form, each with the same 7 assessment tasks measuring a range of concepts from the 4th grade Inquiry Project curriculum. Each task addressed one core matter concept, one measurement skill, and required students to provide an argument based on evidence. Responses on the assessments were scored to determine changes in students’ conceptual understanding during the Video ReView program. (See attached assessments.) Student scores were computed by summing their scores on all items. The maximum possible score was 35. Subscores were also calculated for three subtests: Matter (9 of 35 score points), Measurement (12 of 35 score points), and Argumentation (14 of 35 score points).

Impact

1. Context of the Research

This report summarizes key findings from pilot research with one cohort of teachers participating in the Empowering Teachers Through VideoReView project during 2016-2017. This project is a four-year research and development initiative funded by the National Science Foundation (#1415898) to develop teachers’ capacities in noticing and responding to their students’ thinking in science. The VideoReView program involves school-based, video-supported professional learning, and an easy-to-use technology for teachers to capture and study their own classroom discussion videos.

In this program, teachers participate in a four-part professional learning sequence – PLAN, ENACT, STUDY, and MEET (PESM). First teachers use a discussion planning tool to PLAN science discussions in the classrooms. The tool asks them to identify learning goals and discussion questions, and to anticipate students’ ideas and their possible teaching moves in response. Then, teachers ENACT the discussions in their classrooms, and use technology—a camera and software—to record the discussions. Next, teachers use the software to STUDY independently videos of their science discussions. In studying their videos, teachers attend to and analyze students’ ideas and reasoning related to the learning goals. Teachers also use the software to prepare video cases to discuss with colleagues for deeper reflection. Finally, they MEET with school-based colleagues in primarily teacher-led, school-based “Video Clubs” to discuss the cases, and to consider implications for their teaching.

2. Research Focus and Questions

The purpose of the VideoReView research was to study how school-based, video-supported professional learning helped teachers to notice and respond to students’ thinking in science. As teachers participated in the professional development program, the research examined changes in four areas of teachers’ and students’ learning: (i) teachers’ noticing of students’ thinking as they study classroom videos; (ii) teachers’ facilitation of classroom science discussions; (iii) students’ participation in science discussions; and (iv) students’ conceptual understanding in science Specifically, the following questions guided the research:

- Does participation in the VideoReView program improve teachers’ attention to and interpretation of students’ thinking, and pedagogical decisions based on students’ thinking?

- Does participation in the VideoReView program improve teachers’ facilitation of discussions to promote students’ learning?

- Does students’ participation in science discussions improve as teachers participate in the VideoReView program?

- Does students’ conceptual understanding in science improve as teachers participate in the VideoReView program?

3. Research Method

3.1 Research Participants

Eight elementary grade science teachers from two suburban schools in Massachusetts formed the first cohort participating in the VideoReView professional learning program in 2016-2017. The teachers taught upper elementary grades (grades 3-5). All except one teacher were new to the program. The VideoReView program was implemented separately in each school site over approximately 10 weeks. Each school team had four teachers and they led Video Club meetings with colleagues in their respective schools. Data for research purposes were gathered from the teachers as they participated in the VideoReView program.

3.2 Data Sources

Multiple sources of data were used to address the research questions: (i) transcripts of audio recordings of ‘Think Aloud’ study meetings in which teachers met one-on-one with a researcher, and commented on what they noticed while reviewing their own videos; (ii) transcripts of audio recordings of video club meetings in which teachers discussed video cases with their colleagues; (iii) transcripts of video recordings of classroom science discussions enacted by the teachers; (iv) transcripts of audio recordings of exit interviews with each teacher; and (iv) students’ responses on written pre-post science assessments

4. Data Analyses and Findings

This section summarizes data analyses and presents key findings from the research.

4.1 Changes in Teachers’ Noticing of Students’ Thinking during Independent ‘Think Aloud’ Study Meetings

The transcripts of four ‘Think Aloud’ meetings from each of four teachers in one school were analyzed to identify what teachers noticed in their own videos, and how they made sense of their observations. The transcripts were analyzed using a formal coding scheme developed deductively from literature on teacher noticing, and inductively from data.

Overall, during both early and late ‘Think Aloud’ meetings, the teachers showed sophisticated capacities in noticing their classroom interactions. Specifically, they had a high focus on students’ science thinking in their commentary. When teachers noticed matters of pedagogy, most of their comments involved connecting science pedagogy with students’ thinking. Further, teachers adopted primarily an interpretive stance in analyzing their videos, attempting to unpack and make sense of students’ thinking, as opposed to simply describing or evaluating what they heard. Finally, teachers also commented mainly on specific ideas and reasoning they heard from their students, as opposed to making general comments about the class as a whole or their topic or concepts in the discussions.

There was significant variability among teachers with respect to their focus on noticing students’ science thinking, matters of pedagogy, and their stance in analyzing videos. Specifically, some teachers noticed more student thinking in the videos than others. Teachers also differed in their attention to pedagogical matters, commenting to varying extents on generic pedagogical issues, science specific pedagogy, or connecting science pedagogy with students’ thinking. Finally, teachers differed in their attempts to interpret or unpack students’ science thinking, as opposed to simply describing or evaluating the ideas they heard.

This sample of teachers was already showing high levels of teacher noticing early in the program across all dimensions. One surprising finding was that teachers focused significantly less on students’ thinking in the later study meetings than in the earlier ones (96.35 % earlier meetings vs. 84.10% later meetings). The other dimensions of teacher noticing (pedagogy, stance, and specificity) were not significantly different in later vs. earlier meetings. These findings have implications for designing supports to sustain teachers’ focus on students’ thinking across their video study.

4.2 Changes in Teachers’ Noticing of Students’ Thinking during Video Club Meetings

The transcripts of teachers’ Video Club meetings across the two school-based teams were analyzed to study changes in what teachers noticed in the presented video cases, and how teachers made sense of their observations. The formal coding scheme used to analyze the Video Club transcripts was similar to the one used to analyze transcripts of teachers’ Think Aloud meetings.

The data analysis revealed mixed findings, some more desirable than others. Across the two school teams, teachers showed a high focus on discussing students’ science thinking, and this focus increased in the later video club meetings. Similarly, while discussing pedagogy, teachers’ attempts to connect science pedagogical matters to students’ thinking also increased over time. On the other hand, changes in teachers’ analytic stance and the level of detail in their commentary were contrary to the program’s intentions. Although the interpretive stance was predominant in the early meetings, teachers made fewer attempts to interpret students’ thinking in later meetings. Also, teachers’ early meetings were predominantly about specific ideas and reasonings of students, but fewer of their comments involved this level of specificity in the later meetings. Although none of these differences over time is statistically significant, the findings provide insights into revising supports in the VideoReView program for teachers’ professional learning.

Additionally, a key finding was that the stance of teachers’ noticing during Video Club meetings differed significantly based on the teacher presenting the video case. Some teachers’ video cases were associated with interpretive discussions more than others. In-depth analyses of the data will examine the kinds of video case questions or issues that teachers presented, and their possible connections to the nature of the Video Club discussions. This finding has implications for guiding teachers in crafting productive questions for their video cases.

4.3 Changes in Teachers’ Facilitation of Classroom Discussions

Transcripts of four classroom discussions for each of the eight teachers were analyzed to study changes in teachers’ responsiveness to students’ thinking as they facilitated science discussions. The transcripts were analyzed based on a formal coding scheme developed deductively from literature.

The data analysis indicated that during both early and late discussions, teachers showed a high level of responsiveness towards their students’ thinking, engaging in uptake of students’ ideas, probing those ideas, or asking students to respond to their peers’ ideas. Further, consistent with the program’s expectations, in later discussions, a higher percentage of teacher turns were responsive to students’ science thinking. Additionally, during responsive turns, teachers were more likely to “uptake” a student’s idea, but less likely to probe the students for more information in later discussions than in earlier discussions. Although none of these differences is statistically significant, the findings are promising and indicate areas of growth that can be enhanced in subsequent redesign and implementation.

4.4 Changes in Students’ Participation in Classroom Discussions

Students’ participation in four science discussions for each of the eight teachers was analyzed with a formal coding scheme based on electronic tags of the ‘Science Lens’ in the VideoReView software tool, and on prior research from the NSF-funded Talk Science project (#0918435). The data analysis showed that during both early and late discussions, students were highly engaged with the science content of the discussions, with most of their comments contributing science ideas that were related to the underlying learning goals. Further, in later discussions, a higher percentage of students’ comments involved using science concepts and principles to support their ideas; using everyday experiences to make sense of scientific ideas; addressing their peers’ ideas; and applying their ideas to new contexts.

A surprising finding was that students used evidence from their classroom investigations less frequently in articulating their reasoning in later discussions than in earlier discussions. This result suggests examining more carefully the nature of discussions enacted later in the program, and the extent to which students had opportunities to work with data and evidence during those discussions. Although none of these differences is statistically significant, most of the findings are in the expected direction and point to areas of growth than can be enhanced in subsequent redesign and implementation.

5. Teachers’ self-reported experiences (Exit Interviews)

In the exit interviews, teachers reported several areas of growth in their classroom practice as a result of their participation in the VideoReView program. Analyzing classroom videos helped teachers become aware of students’ alternative conceptions or challenging ideas that needed to be addressed. They realized that it was not always necessary to plan new investigations or lessons to do so; rather that students’ ideas could be addressed even with follow up questions and additional time to think during discussions. Teachers also gained insight into how students were reasoning, particularly with evidence from science investigations, and identifying areas of focus for planning their instruction.

Furthermore, teachers reported that listening to students’ thinking on video helped them to listen for depth of students’ understanding in the moment during classroom discussions, acknowledging that video allowed them to practice this skill in less rushed settings. Finally, teachers described shifts in their practices at planning science discussions. Specifically, they reported anticipating students’ ideas and how their ideas could be elicited at the beginning of a lesson.

6. Changes in students’ conceptual understanding

Two fourth-grade classrooms (N = 35) from one school participated in a written pre-and post-assessment measuring their understanding of concepts taught in the Inquiry Project curriculum, which was the curricular unit taught in these classrooms during the VideoReView program. There were statistically significant differences in student scores between the pre- and post-assessment, with respect to both the overall score and the three sub-scores: Measurement; Matter; and Argumentation. Post-assessment scores were all significantly higher than their pre-assessment counterparts, both for the overall score and for the separate sub-scores.

7. Conclusions & Implications

The findings gathered from implementing the professional learning program with the first cohort of teachers generated key implications for both revising the professional learning supports, and for its associated research. Specifically, supports will be redesigned to guide teachers’ video study, which will differ markedly from the ‘Think Aloud’ meeting protocol that was used in the first round of implementation. The original ‘Think Aloud’ protocol was challenging due to its rather artificial nature of interrupting the teachers every two minutes for their commentary on the video, and due to repetitive and inefficient nature of the video viewing tasks for the teachers. Therefore, a revised Video Study Guide will be provided to help teachers engage deeply with fewer exchanges in the video, and the Guide will prompt teachers explicitly to comment on students’ ideas and reasoning. It is hoped that the explicit language in the Guide about students’ thinking will draw and sustain teachers’ attention to students’ science ideas and reasoning.

Additionally, teachers will be provided with video resources on the project’s website to support their focus on students’ thinking. For example, video resources will exemplify each of the four parts of the PESM professional learning sequence, revealing to teachers how students’ science thinking serves as the foundation for each step of their professional learning. These resources will feature experiences of other teachers who served as co-developers of the VideoReView program.

Regarding implications for the associated research, three aspects of the study should be noted. First, the sample size was small and many teachers who participated in the study showed remarkably sophisticated capacities in noticing students’ thinking even at the beginning of the program. These factors combined may have made it difficult to detect statistically significant changes in teachers’ learning. Second, although statistically significant changes were not detected for most outcomes of interest, the findings for some of the outcomes were consistent with the program’s goals. It is conceivable that implementing the program with teachers who show greater variation in skills may allow greater opportunity for change in practice, particularly during the short period during which the intervention is likely to occur. Teachers participating in the program in 2017-2018 will represent a wider range of experience. The cohort will comprise teachers from urban, suburban, and rural schools in Massachusetts and Vermont, thus extending the program to various settings.

Third, the study did not involve a true baseline/pre-intervention and post-intervention measure of teachers’ skill at noticing and responding to students’ thinking. Rather, the first set of data were gathered after the professional development program started, and the final set of data gathered were still part of the program. Therefore, in implementing the program with the second cohort of teachers, baseline data will be collected prior to the launch of the professional development, and data will also be collected after the program ends. The baseline data will be compared to the post-intervention data, as well as with teachers’ noticing and classroom practice as these occur during the program. These comparisons will provide summative information on the impact of the program, and a more qualitative understanding of how the program influences teachers’ noticing and instruction.