What can we learn about rocks by observing them carefully?

Plan Investigation 1.2

Have you ever come across a rock that seemed too interesting to pass by, picked it up, and slipped it into your pocket? Chances are your students have, too.

In this investigation, students focus on a set of four rocks. They use magnifiers to explore the rocks closely and they record their observations about one of the rocks in their notebook. After sharing their observations, students develop some general statements that apply to all the rocks.

By the end of this investigation, students will understand that rocks are objects that are composed of various materials called minerals. They will also begin to distinguish properties of rocks (e.g., size and weight) from properties of the minerals they are made of (e.g., color and sparkle).

Learning Goals

- Understand the difference between rocks (objects) and minerals (the materials that rocks are made of)

- Discover some properties of rocks and minerals by looking at them closely

| Sequence of experiences | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ask the question | All Class | 5 Mins |

| 2. Explore the rocks | Small Groups | 15 Mins |

| 3. Share data | All Class | 10 Mins |

| 4. Make meaning | Discussion | 15 Mins |

Materials and Preparation

- Post the investigation question in a place where all students can see it.

- Make a class chart for recording observations about rocks and post it in a place where all students can see it; an example is found in Step 3.

- 1 plate of 4 rocks: sandstone, granite, conglomerate, and basalt; this set of rocks will also be used in the next investigation

- 2 Rock Reference sheets

- 4 magnifying glasses

- 1 piece of quartz, distributed in Step 4

1. Ask the question

Recall some of the earth materials the students investigated last time — e.g., sand, clay, shells, and oil. Let students know that today they will investigate one of the earth materials more closely — rocks.

Invite students to share their experiences with rocks.

How many of you have found an interesting–looking rock somewhere, picked it up, and taken it home?

Introduce the investigation question:

What can we learn about rocks by observing them carefully?

Have students brainstorm some ideas. Maybe they will indicate properties like size, weight, color, texture, temperature, or “sparkliness.”

Let students know that scientists who study rocks closely are called geologists.

Did you know? Rocks can be ancient–hundreds of millions of years old. They are the oldest things we’ll ever touch. But some rocks are being formed right this minute, they are being made by volcanoes, out of lava.

2. Explore the rocks

Distribute a tray of materials to each group, but hold back the quartz for now. Write the names of the four rocks on the class chart and pronounce them for the class:

Sandstone … Granite … Conglomerate … Basalt.

Allow a few minutes for students to pass the rocks around and identify each one, then ask students to hold on to whichever rock they have.

Now issue a challenge:

- You have a rock. You have a magnifying glass. You have your senses. Use all your powers of observation to learn everything you can about the rock you are holding.

- List at least six observations about your rock. Write your observations in your notebook. Include some drawings, too.

Have the students work in pairs. Though each student will describe only one rock, comparing the two rocks might elicit more observations.

As you circulate among the groups, draw attention to the different materials the rock is made of.

- Are you talking about the black, bumpy stuff or the white, shiny stuff?

- Is the rock made of the same stuff all the way through?

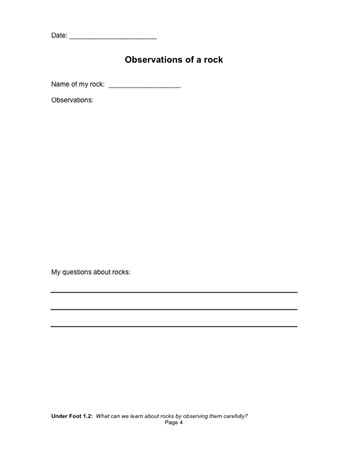

Make sure students are recording their observations in their notebooks [Observations of a rock], and that they are distinguishing their "data" from their "ideas about data."

Distinguishing "data" from "ideas about data." Help students see the difference between data, which is simply a record of observations, and ideas about data, which include thoughts, questions, predictions, speculations, and hypotheses. “There are sparkly flakes in the rock” is data. “I think the white rock may be heavier than the gray rock.” is a prediction.

Encourage students to record both kinds of information in their notebooks, but to distinguish them in some way. They might put data on one side of the page and ideas and questions on the other. Or they might use colored pencils, and/or a code in the margin: D for Data, I for Idea; Q for Questions.

As the students finish up their observations, recall the investigation question:

What have we learned about rocks so far, just by observing them carefully?

3. Share the data

Compile students’ observations about the four rocks on the class chart. To speed the process, take one rock at a time, asking each student who observed that rock to provide a different observation.

What else did you observe about [granite]?

As students contribute their observations, make sure they distinguish between their data and their ideas about the data. Let them know they will discuss ideas and questions about the data in a minute. For now, they should simply list their observations about such things as color, size, texture, weight, shape, and composition. Let the students know that these characteristics of rocks are called properties.

Two types of observations are central to the goals of this session. It’s likely that students will include them, but if not, ask if anyone made an observation about:

- The number of different materials in their rock (leading to an understanding that rocks are made of minerals)

- The size, shape, or weight of the rocks themselves (reinforcing the distinction between an object and its materials)

Remind students that each section describes the properties of a particular rock. Next they will talk about the properties that all the rocks have in common.

How scientists share data. As the students share their data, let them know that scientists spend a great deal of their time doing the same thing. Sharing data creates a larger set of data, inspires new ideas, and builds knowledge. Some of the ways scientists share their data are through e–mail and teleconferencing, at conferences, and in publications.

4. Make meaning

Purpose of the discussion

The purpose of the discussion is to elicit claims about rocks that can be supported by students‘ observations of four kinds of rock. Focus the discussion on the investigation question.

Engage students in the focus question

Revisit the investigation question:

What can we learn about rocks by observing them carefully?

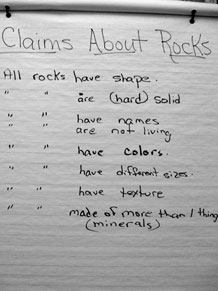

Ask students to look at the class data and think about what they can say about all the rocks on the list, not just one kind. The goal is to move from observations about individual rocks to general statements — or claims — about all four rocks.

Take observations one at a time and see if they are generalizable. For example:

You observed that basalt is black. But are all rocks black? Some of you observed rocks with other colors. What can we say about color that is true for all of these rock samples?

After eliciting ideas, try for consensus:

Can we agree on this statement: Rocks can be different colors, including gray, white, red, and black?

Create a new class chart: Claims About Our Rocks.

What is a claim? A claim is a statement that is believed to be true, but not proven to be true, and that is based on observations or data. When someone makes a claim, they should be prepared to identify the data on which they base it. As you develop the class list of claims, pause periodically and ask: “What evidence do we have to support this claim?”

Based on our observations of granite, basalt, conglomerate, and sandstone, what else can we claim about rocks?

Continue the discussion until the class has agreed on six or eight statements that hold true for all four rocks. Point out that while the claims may be true for these four rocks, they may not be true for every rock in the world.

Summarize the discussion

Refer to the Claims About Our Rocks chart.

Explain that the materials that make up rocks are called minerals. Let the students know there are thousands of different minerals on Earth, and that quartz is one of the common ones.

Distribute a piece of quartz to each group.

- Is there any of the mineral quartz in your rock?

- What properties does the quartz have that the rest of the rock doesn’t have?

As you recap the investigation, check for understanding of these two points:

- Rocks are objects made of materials called minerals

- Rocks and minerals have observable properties

There is a notebook page for students to record the class's claim about rocks. [Properties of rocks]